The 2000 Egyptian legislative election was held at the height of President Hosni Mubarak’s rule, and drew a spotlight onto the nature and limitations of his regime’s control over Egypt.

Transcript:

Hello and welcome to episode 6 of the History of Elections Podcast, where we will be looking back at the 2000 legislative election in Egypt. Held at the height of President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year authoritarian rule, the election drew a spotlight onto the nature and, perhaps, the limitations of Mubarak’s rule over Egypt.

November, 2000. The United States is thrown into political chaos after the presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore hinges on a recount in Florida; Alberto Fujimori, the autocratic president of Peru, flees the country over allegations of corruption and crimes against humanity; Jharkand is created as the 28th state of India, having been carved out of Bihar; a horrific funicular fire in the Austrian Alpine mountains kills 155 people; the first long-term expedition is launched to the International Space Station, beginning 25 years and counting of continuous activity; and, in Egypt, voters go to the polls to nominally elect their next parliament.

Background

By the turn of the millennium, Egypt had been ruled by its president, Hosni Mubarak, for 19 years. Mubarak was the inheritor of the authoritarian regime that had been established by Gamal Abdel Nasser following the 1952 coup, which had overthrown the Egyptian monarchy and brought an end to British imperial influence in Egypt. The coup, part of what has come to be known as the Egyptian Revolution, had a profound effect on the Arab World—as we discussed two episodes ago, the ideas of Pan-Arabism and Nasserism heavily influenced the Ba’athist states that emerged in Syria and Iraq in the 1960s.

Nasser ruled Egypt as a presidential one-party state until his death of a heart attack in 1970, at the age of just 52. The sole legal party went through several iterations and, by the time of his death, was known as the Arab Socialist Union. It embodied the core ideas of Nasserism: pan-Arabism, nationalism, socialism, anti-imperialism and anti-Zionism. He was succeeded by his vice president and the former parliamentary speaker, Anwar Sadat, who emerged as a compromise candidate between competing powerbrokers within the regime.

Upon consolidating power in his own right, Sadat pursued a programme of relative liberalisation of both the Egyptian economy and political system. The country was opened up to foreign investment and new incentives for private enterprise were introduced, moving away from the strict socialist underpinnings of Nasser’s rule.

Sadat purged the government of the most hardline Nasserists and relaxed restrictions on the country’s substantial Islamist movement, which was led by the Egyptian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, who we last met in Syria in episode 4. The Muslim Brotherhood had been founded in 1928 but had been banned under Nasser. Although Sadat did not formally unban the organisation, he initially showed greater tolerance for its activities, hoping to gain an ally against parts of the political left that opposed him.

He implemented a new constitution that, on paper, cemented the rule of law, but also strengthened the powers of the presidency. His most notable political reform was to end the one-party system, with the first multi-party election in 29 years taking place in 1979. The Arab Socialist Union itself was reformulated as the National Democratic Party, or NDP, dropping the titular commitment to Arab socialism and committing, on paper, to democracy—an important ideological move as the party shifted to a more centrist position, though it maintained its secularist orientation.

Nevertheless, Sadat and the NDP kept a firm hold on the state, and the new multi-party elections were not genuine contests for political power; rather, the presence of opposition parties was intended to provide a democratic façade to help legitimise the regime, both domestically and internationally—what Eberhard Keinle described as “a mere update of authoritarianism.” Indeed, at around this time, Sadat is alleged to have described Nasser and himself as “the last pharaohs”.

Presidential elections remained plebiscites with just one candidate on the ballot, who was nominated by a two-thirds vote of the legislature—similar to the system used by Ba’athist Syria that I described in episode 4. Such a system was clearly designed with the assumption that the regime would always control a two-thirds majority in the legislature.

It would be foreign policy that most shaped and determined the fate of Sadat’s presidency. In the context of the Cold War, he moved Egypt away from the Soviet orbit and pursued closer ties with the United States. After Egypt suffered a third military defeat against Israel in 1973, Sadat took the controversial step of seeking a unilateral peace agreement. This culminated in the Camp David Accords of 1978. Brokered by US President Jimmy Carter, the accords saw Egypt formally recognise Israel and agree to a peace treaty in exchange for regaining the Sinai peninsula—which had been occupied by Israel since 1967—and, further down the line, substantial American military aid.

Sadat won the Nobel Peace Prize for the peace treaty but was fiercely condemned across the Arab World for unilaterally recognising Israel, particularly in the absence of a solution to Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Egypt was suspended from the Arab League—the body’s headquarters relocating to Tunisia—and Egypt stopped receiving oil subsidies from Gulf states. Egypt’s role as a figurehead for the Pan-Arab movement came to a decisive end, creating a void that the Ba’athist states of Syria and Iraq—and also, to an extent, Saudi Arabia—would attempt to fill.

The peace agreement also ended Sadat’s hopes of reconciling with Egypt’s Islamist movement; fiercely condemned by the Muslim Brotherhood, he resorted to renewed persecution of the organisation and other Islamist groups. In particular, the state began to crackdown on jihadist organisations, which had grown in influence throughout the 1970s and explicitly plotted to overthrow Sadat.

These developments precipitated Sadat’s downfall. During a military parade in 1981 to mark Egypt’s initial victories against Israel during the 1973 war, Sadat was assassinated during an attack by members of one such jihadist group—the Egyptian Islamic Jihad—who were motivated by the peace treaty with Israel. The assassination was intended to spark a wider uprising that would overthrow the secular state, but the only rebellion to actually take place, in the city of Asyut, was quickly put down by security forces.

Mubarak’s Presidency

This brings us to Hosni Mubarak. After rising through the ranks of the Egyptian air force, Mubarak had become Sadat’s vice president in 1975. Mubarak had gained national fame for his role in Egypt’s initially successful offensive against Israel in 1973 and began to portray himself as part of a younger generation that had come to prominence in the post-revolutionary era—he was himself ten years younger than both Sadat and Nasser.

Mubarak, who was also injured during the attack on Sadat, assumed the presidency on Sadat’s death, becoming Egypt’s fourth president. A presidential election was arranged within a week with Mubarak the sole candidate on the ballot; official figures showed that he “won” the referendum with 98% of the vote.

Mubarak went on to “win” uncontested presidential elections in 1986, 1993 and 1999. His vote share in those elections fell to 97%, 96% and then all the way down to 93% in 1999. I suspect he was not unduly concerned by that decline, but it did mark a trend.

Again, to draw comparisons with the Syrian system that I described two episodes ago, the regime cast a somewhat less tight net over the political movements that were allowed to contest elections. Egypt was generally perceived to be ruled by a relatively more liberal and constitutional system than its Syrian counterpart, an image that sometimes suited Mubarak’s regime.

At various points during his rule, Mubarak’s Egypt was cited as an example of a gradually democratising state. Such assessments veered on the naïve—or, on the part of some American analysts, displayed motivated reasoning to support an allied government. Other commentators and political scientists argued that the Middle East had proved immune to what was sometimes described as the “third wave of democratisation” from the 1970s that occurred across Europe, Latin America and Africa.

According to the V-Dem electoral democracy index, which grades countries based on how free and fair their elections are on a scale from 0 to 1, by 2000, Egypt scored just 0.22. That was ahead of the score of 0.15 in Syria—which, in the same year, elected Bashar al-Assad to his first term of office—but it was well below the global average of 0.49, or the African average of 0.36. Egypt’s annual electoral democracy rating had remained pretty steady under Mubarak.

However, as president Mubarak expanded the security state and continued to suppress Islamist movements, especially from the 1990s. He himself survived multiple assassination attempts, including an attack in Port Said in 1999, when he was injured by an assassin wielding a knife. Mubarak also oversaw a continuing military campaign against Islamist militants, with an annual death toll in the 1990s rising to the hundreds.

The regime made use of a continuous state of emergency that had been enacted after Sadat’s assassination to bypass constitutional protections for human rights. Arbitrary arrests and the use of torture was common and there was widespread detention of opponents of the regime and dissidents, as well as increasing use of military trials. Newspapers were regularly shut down, public demonstrations banned and human rights activists jailed.

The regime also exercised wide control over Egyptian civil society. It controlled the appointment of university deans and village leaders while ensuring subservient leadership among trade unions and professional organisations. Islamic institutions were also controlled by the state—religious leaders gained the nickname of “pulpit parrots” for their promotion of regime narratives.

Mubarak portrayed himself, particularly to the west and United States, as a modern, secular bulwark against radical Islamism seizing control of the Arab World’s most populous country. That argument had been strengthened by the precedent of Algeria, where a secular regime had been fighting a bloody civil war against a popular Islamist movement since 1992. However, Mubarak lacked the ideological zeal and purpose of Nasser or even Sadat. William Cleveland and Martin Bunton described Mubarak’s regime as one “that had no purpose other than to stay in power” and Mubarak himself as a president who “inspired little popular confidence.”

The economy grew rapidly under Mubarak. He maintained the mixed-economy approach developed under Sadat with a heavy emphasis on the public sector; in 1986, 35% of the labour force was employed by the state. Between 1981 and 2000, Egypt’s GDP nearly tripled, a slowdown in the early 1990s notwithstanding. However, the country’s booming population—rising from 45 million to 73 million in the same period—meant that per capita GDP growth less marked. There was also widespread corruption; by 2011, Mubarak’s family was estimated to be worth 70 billion US dollars.

Foreign policy remained a core concern for Egypt under Mubarak’s leadership. He upheld Sadat’s peace treaty with Israel and continued to benefit from American military aid, which was numbered in the billions of dollars. Notably, Egypt maintained the peace treaty and declined to intervene when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982. Nevertheless, relations remained cold. He visited Israel only once, in 1995, to attend the funeral of Israel’s assassinated Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin—leaving the country after just a few hours. He also re-established ties with the Soviet Union in the 1980s, seeking to avoid being tied entirely to either Cold War superpower.

Mubarak rebuilt relations with the Arab world, particularly Saudi Arabia. This effort was aided by the Iranian revolution, after which Egypt loosely aligned itself with forces that were opposed to the new Iranian government. Mubarak provided military and economic support to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq during its war against Iran.

Legislative Elections under Mubarak

Since 1980, Egypt had possessed a bicameral legislature, with the lower house People’s Assembly and the upper house Shura Council. In the People’s Assembly, 10 of about 450 MPs were appointed by the president, while a third of the Shura Council’s members were appointed. Each legislature was elected in separate elections. The parliament possessed very few real powers and lacked the capacity to place a check on the president’s power.

Mubarak’s National Democratic Party remained dominant in legislative elections, although candidates from alternative parties and independent candidates were tolerated to varying degrees. Mubarak continued the façade of political liberalisation and elections became slightly more open than during the Nasser and Sadat eras. For example, he unbanned the liberal and secular Wafd Party—one of Egypt’s oldest parties, which had played a key role in Egyptian politics in the 1920s and 1930s. After some legal difficulties, the New Wafd Party began contesting elections from 1984. In the 1987 legislative election, about 20% of elected MPs represented opposition parties, and the number of legal parties in this period rose to 16.

Nevertheless, no serious opposition to the regime was tolerated. Indeed, after a period of initial openness during the 1980s, Mubarak began to reintroduce controls on political activity and use methods such as patronage and electoral fraud to prevent any opposition movement from growing too influential. No applications to form a new political party were accepted by the state’s Political Parties Committee in the 1990s. One such rejection was for a proposed “Center Party” aimed at bringing together politically moderate Muslims and Christians in support of democratic reform. By 1995, the NDP and allied independent MPs had recovered to 94% representation in the People’s Assembly.

For the regime, elections provided opportunities to legitimate its rule, re-establish patronage relationships and distribute resources to supporters. Mona El-Ghobashy described Mubarak-era elections as “rare moments of open, if unequal, political competition between government and opposition,” which opposition movements generally considered to be worth participating in, particularly after a failed boycott in 1990.

Meanwhile, the regime once again attempted to pursue a rapprochement with the Muslim Brotherhood, seeking to reconcile moderate Islamists in order to isolate more radical movements. The Muslim Brotherhood still faced some periodic repression but its professional, charitable and student networks were able to operate to various degrees and began building an increasingly large following across Egyptian society.

The Muslim Brotherhood was not allowed to formally contest elections, but, from the mid-1980s, some of its members were permitted to contest legislative elections as independent candidates, some of whom were even able to win election. By the end of the decade, independent Islamists formed the largest opposition bloc in the People’s Assembly. The rapprochement would be partially reversed in the 1990s, as Mubarak’s attitude towards the Muslim Brotherhood shifted from viewing it as a potential ally to a potential threat, but its members continued to be able contest elections as independents.

The 2000 Egyptian legislative election

In 2000, Egypt prepared to hold its fifth election to the People’s Assembly since Mubarak assumed the presidency. The election took place against the backdrop of a mobilised constitutional reform movement. In 1999, a group calling itself the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee brought together members of the Muslim Brotherhood, Nasserists, communists, liberals and economic conservatives to demand free elections, direct presidential elections and an end to restrictions on the media and political organisation. The regime thoroughly rejected those demands, arguing against any moves that would “divide” the country.

The election was characterised by significantly greater judicial oversight than past elections. That followed a ruling by Egypt’s Supreme Constitutional Court in July 2000 that polling stations and ballot counts must be monitored by judges. The ruling originated from a court case brought by an independent candidate in the 1990 legislative election who argued that oversight by civil servants instead of judges—who tended to operate with greater independence from the government—violated Sadat’s 1971 constitution. The Supreme Constitutional Court’s decision was a rare victory for Egypt’s liberal civil society, which had frequently attempted to utilise provisions in Sadat’s constitution to secure legal protections via litigation. Nevertheless, the regime immediately began to explore ways of circumventing the ruling, as we will see.

To comply with the court ruling and ensure capacity for judicial oversight over the country’s 15,502 polling stations, the election was broken into three stages. The first 150 seats were elected on 18 October in northern Egypt; the next 134 seats were elected in eastern and southern Egypt on 28 October; and the final 156 seats in central Egypt and Cairo were elected on 8 November. The staged system of voting had the unintended effect of allowing the opposition to try out tactics and test messages in the first stage that could be utilised to better effect in later stages, providing something of a training ground for opposition candidates.

Since 1990, the People’s Assembly had been elected using a plurality district system rather than proportional representation, which had been ruled unconstitutional in another judicial intervention. That decision had the perhaps surprising outcome of strengthening prospects for opposition candidates by making independent candidacies more viable, thereby opening the door for coordinated campaigns by members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The NDP was led into the election by Egypt’s new Prime Minister, Atef Ebeid, who had been appointed to office by Mubarak the previous year. A former professor of business at Cairo University, Ebeid had served in several ministerial roles from the 1980s. The NDP’s candidates were chosen in a tightly controlled process by the party’s general secretariat, although several unsuccessful candidates nonetheless chose to run as allied independents—more on them shortly.

Earlier in the year, President Mubarak’s 29-year-old son, Gamal—named after Nasser—had decided to enter politics. After years working in banking and private equity in the United States and Britain—a further indication of Egypt’s westwards orientation that had continued since the Sadat era—Gamal Mubarak was appointed to the NDP’s general secretariat and contributed to the party’s election campaign. Gamal would play a growing role within the NDP over the coming decade, raising speculation that, as in Syria, Mubarak planned to groom his son to succeed him. If that was the plan, it would ultimately be thwarted by the 2011 revolution.

Various other political parties contested the election. Among the more notable opposition parties was the New Wafd Party, the liberal, secular party described earlier, which had been contesting elections since 1984. The election was also contested by the National Progressive Unionist Rally Party, founded in 1977 as a left-wing breakaway of the Arab Socialist Union. A Nasserist party, it endorsed the principles of secularism, Marxism and Arab nationalism, and it sought to promote the ideals of Egypt’s 1952 revolution.

Another Nasserist party was—as the name suggests—the Arab Democratic Nasserist Party, which broke away from the National Democratic Party and also claimed to represent the legacy of Nasser. Finally, the election was contested by the Liberal Socialists Party. Initially founded in 1976 as a right-wing faction of the Arab Socialist Union, the Liberal Socialists—as the name very much would not suggest—ended up becoming a moderate, economically liberal Islamist party.

Multiple independent candidates also contested the election, including, as discussed earlier, some failed NDP candidates and members of the Muslim Brotherhood, who were prohibited from formally contesting as an organised movement or political party. Muslim Brotherhood independent candidates were identified on the ballot by their slogan: “Islam is the solution.” However, some Muslim Brotherhood activists were arrested by the regime during the run-up to the first round, while many of the movement’s donors—a group that included several wealthy businesspeople—were harassed and threatened.

Just 24.6 million of Egypt’s 73 million residents were eligible to vote, partly due to Egypt’s overwhelmingly young populace, with almost half its population being under the age of 20.

Results

The advent of judicial oversight ensured that there was markedly less direct fraud than in previous elections, a development that appears to have taken Mubarak by surprise. Judges prevented unregistered pro-NDP voters from casting ballots and refused to allow police officers to transport ballot boxes to election counts, removing some of the most blatant opportunities for ballot rigging. Nevertheless, the regime remained able to influence the election outside of polling stations by intimidating voters and candidates, destroying opposition campaign material and arresting opposition activists. The NDP’s structural advantages and state dominance ensured that the overall results were not a surprise.

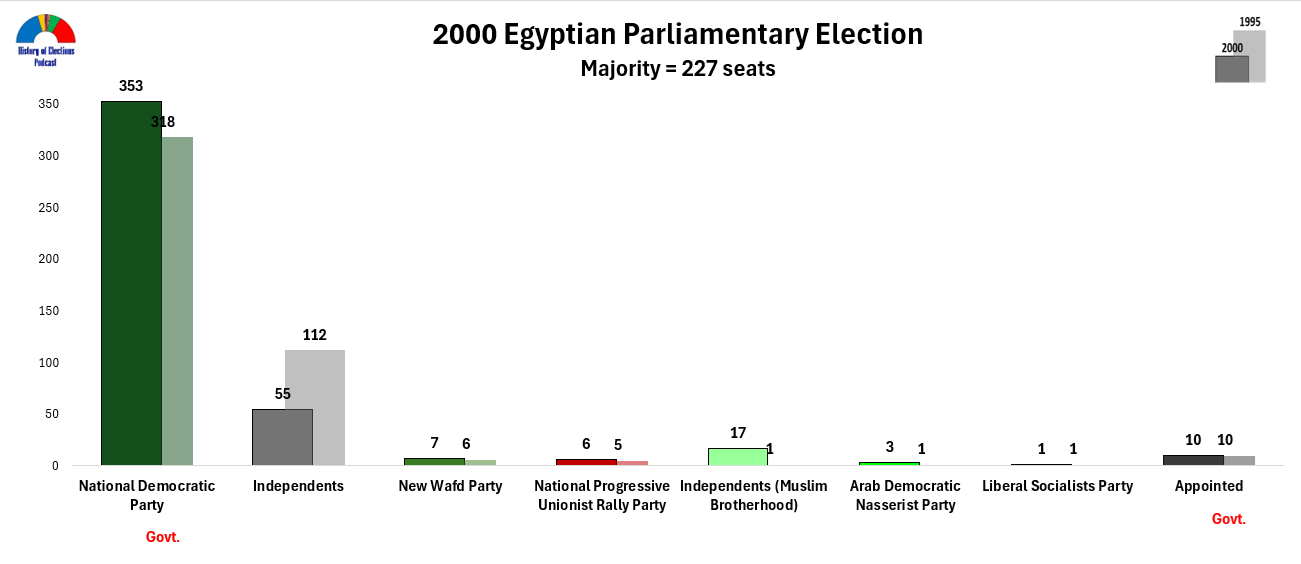

Given the fluidity in party allegiance and the overlap between candidates who stood as NDP-aligned independents, tallies for the election results often vary between sources depending on how exactly they counted. Including independents who were explicitly affiliated with or members of the NDP, the results showed the NDP’s tally rising from 318 seats to 353, representing 78% of the People’s Assembly. Some of those nominal independent candidates were people who had been rejected as formal NDP candidates, but nonetheless acted as de facto NDP candidates and, upon election, became NDP MPs.

However, that rise on paper did not reveal the full picture. Only 38.9% of candidates explicitly contesting under the NDP banner won election, down from 52.6% in 1995. Two-thirds of incumbent MPs were defeated, including eight committee chairs. Although that was largely due to NDP candidates competing against one another in various districts, the trend suggested a growing lack of party coordination—something the NDP would seek to correct later in the decade.

Meanwhile, 72 genuine independents MPs were elected. Again, on paper, that number was down from 113 successful independents who were elected in 1995. But those independent MPs actually represented an enlarged opposition bloc, as a smaller number—just 35—went on to join the NDP after the election. Of the remaining 37 opposition independents, 17 were members of the Muslim Brotherhood, up from just one in 1995. Although not formally members of a party, the group of 17 Muslim Brotherhood independents now comprised the largest single opposition bloc in the new parliament.

With the defection of 35 independent MPs, the government’s seat tally was bolstered to 398, or 88% of seats. Only 12% of MPs truly represented opposition voices—and even they operated within limits that were tolerated by the regime. That was double the proportion of opposition MPs who had been elected in 1995, indicating that the new judicial oversight requirements had resulted in some success in facilitating competitive contests, but the opposition remained firmly locked out of power or influence.

Of the official opposition parties, only 17 of their combined 352 candidates were successfully elected to the People’s Assembly. The New Wafd Party gained one seat, rising to seven seats, as did the National Progressive Unionist Rally Party, which rose to six seats. The Arab Democratic Nasserist Party tripled is representation from one to three seats, while the Liberal Socialists Party retained their single seat. No other party won representation.

The new parliament was overwhelmingly male: 443 of its members, or 98%, were men, with just 11 women elected. Five of those women were among the ten members appointed by President Mubarak in a bid to provide token representation; two of the appointed members were also Coptic Christians, representing Egypt’s largest and main religious minority.

In a further indication of some judicial independence, two results in Alexandria were annulled due to irregularities. Nevertheless, this plainly did not alter the fundamental character of the election, which was an attempt to legitimate the ruling regime while preventing any genuine contestation for political power.

Aftermath

As usual, the opposition was denied any real influence or ability to shape policy. Instead, it used its minimal representation to help state functions and services work more effectively for their constituents and attempt some basic scrutiny of government policies. After the election, the regime upped its raids and detentions of the Muslim Brotherhood and liberal opposition figures.

Alarmed by the advent of judicial oversight, which had allowed the opposition’s presence in the People’s Assembly to double from 6% to 12%--truly, a threat to Mubarak’s rule—the regime found a loophole to avoid a repeat in municipal elections that were held in 2002, leading to an opposition boycott. Evidently, the opposition rising above 10% representation in the parliament was perceived by the regime as outgrowing its tolerated role of providing a façade of pluralism.

However, the Muslim Brotherhood was able to use the successful election of 17 of its members in 2000 as a springboard for further electoral success. It would mobilise further for the 2005 People’s Assembly election, electing 88 of its members as independent MPs—a sizable opposition bloc, despite the regime’s continued attempts to avoid genuine contests. The regime then responded by placing further barriers on independent MPs to win election and by cracking down on the Muslim Brotherhood, arresting thousands of its members, in yet another reversal in the state’s attitude towards the organisation; it would not be the last.

As in Syria, the Egyptian regime’s close control over the electoral process was unable to insulate it from popular anger and discontent. When the Arab Spring revolutionary wave swept through the region in 2011, Mubarak became the most significant autocrat to fall from power, standing down as part of an army-led transition process. That enabled Egypt to avoid following Syria, Libya and Yemen into civil war.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s popular support—demonstrated by its inroads in the 2000 election—enabled it to briefly gain power in free elections that were held in 2011 and 2012, though that would not last; Mubarak’s successor as president, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, was overthrown in a coup after just a year in power, and Egypt returned to a secular dictatorship under the rule of Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, which remains in power to this day. The Muslim Brotherhood was once again banned, and has not been permitted to play a role in any of the subsequent post-revolutionary elections, which have, once again, been tightly controlled.

As I mentioned earlier, Egypt was often a case study for post-Cold War discussions of democratisation and autocracy. The country was viewed by some commentators and analysts as following the trajectory of economic liberalisation leading inevitably to political liberalisation, an idea that was much more in vogue in the immediate post-Cold War period than it is today. With the benefit of hindsight—although, really, it was fairly obvious at the time—the Mubarak regime was relatively entrenched, and certainly had no intention of relinquishing power or allowing genuine electoral contestation.

Yet, nor was Egypt a static dictatorship. The country did experience periods of limited liberalisation under Mubarak, as the regime relaxed, sought to co-opt parts of the opposition or was thwarted by elements of the judiciary and opposition. Instead of a liberalising country or an unchanging dictatorship, Egyptian politics swung like a pendulum between periods of limited openness and harsh crackdowns, depending on the incentives and vulnerabilities of the ruling elite at the given moment. The 2000 legislative election came at the end of one such period of renewed oppression and, through an assertion of judicial independence, marked a new period of slightly enhanced opportunity for the Egyptian opposition.

And what of Atef Ebeid, the Prime Minister who led the NDP into the 2000 election? He served as Prime Minister for five years, briefly acting as president for two weeks in 2004 while Mubarak received medical treatment in Germany. He was replaced as Prime Minister shortly afterwards—I assume not because of anything he did in those two weeks—and he went on to lead the Arab International Bank. However, he could not escape the drive for accountability that accompanied the 2011 revolution: he was removed from office after Mubarak’s overthrow over corruption allegations and, in 2012, was sentenced to ten years in prison. He died in 2014 at the age of 82.

Bibliography

Al-Awadi, Hesham, In Pursuit of Legitimacy: The Muslim Brothers and Mubarak, 1982-2000 (I.B. Taurus: London, 2004).

Brownlee, Jason, “Democratisation in the Arab World? The Decline of Pluralism in Mubarak’s Egypt,” Journal of Democracy 13.4 (October 2002), pp. 6-14.

Cleveland, William L. & Bunton, Martin, A History of the Modern Middle East (Westview Press, 2013).

Kienle, Eberhard, A Grand Delusion: Democracy and Economic Reform in Egypt (I.B. Taurus: London, 2001).

Petty, Glenn E., “The Arab Democracy Deficit: The Case of Egypt,” Arab Studies Quarterly 26.2 (Spring 2004), pp. 91-107.

Sowers, Jeannie & Toensing, Chris (eds), The Journey to Tahrir: Revolution, Protest and Social Change in Egypt (Verso: London, 2012).